Peak Response: Evolution of a MCI First Responder Mobile App

Francis Li

Peak Response Inc.

San Francisco, California, USA

May 2024

Abstract

Peak Response is an award-winning mobile app for the iPhone designed to provide situational awareness and facilitate communication for emergency medical first responders on scene at a mass casualty incident (MCI). In this report, we describe the evaluation of the app by professional paramedics through a series of drills and the evolution of the app feature set and interface design based on their feedback and observations of its usage. Finally, we share observations and insights from the usage of the app during a large-scale MCI drill that highlights the potential for the Peak Response app to improve how first responders perform in these complex emergency situations.

Background

The original concept and prototype for what would become the Peak Response mobile app was first developed as part of the Tech to Protect Challenge, hosted by the National Institute of Technology Public Safety Communications Research division (NIST PSCR). The contest topic addressed was titled, “Organizing Chaos: Calming Catastrophe by Tracking Patient Triage,” and challenged participants to develop new technology for first responders to use on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI), broadly defined as an emergency situation whose needs overwhelms the available resources, particularly emergency medical service (EMS) providers and hospitals. The original key innovations of Peak Response, then called NaTriage, demonstrated the use of widely available commodity smartphone hardware to scan triage tag barcodes with the built-in camera, to capture and attach patient details and observations using voice-to-text transcription, and to share these details in real-time across all connected devices both on and off scene.

NaTriage was awarded both the Top Overall and Best in Class prizes for the San Francisco region, and would continue with further development to receive a National Award of Excellence as well as Seed and Progress awards as part of the ongoing Tech to Protect challenge. These awards were used to incorporate Peak Response Inc, a public benefit corporation, to further develop NaTriage, now Peak Response, for introduction into the public safety industry and market. This continued development has also been funded by a Public Safety Innovation Accelerator Program grant award from NIST PSCR.

Peak Response App Overview

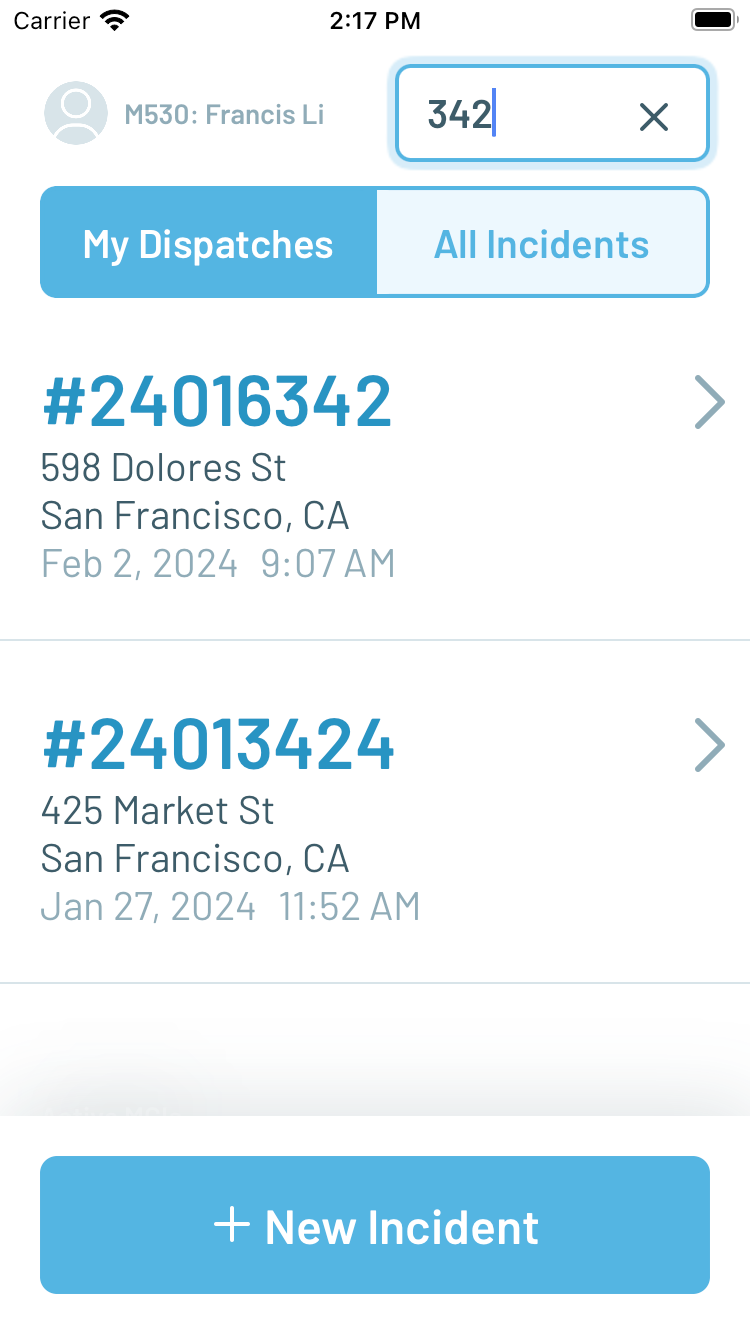

The Peak Response mobile app is designed to be used by EMS responders both as part of their day-to-day workflow and on scene of a MCI. In any daily dispatched run, the Peak Response app can be used to gather initial patient observations and data which is stored in a standardized electronic record compatible with electronic patient care reporting (EPCR) systems. This includes data such as patient demographics and medical history as well as vitals and any initial procedures performed or medications administered. As such, the Peak Response app can replace pen-and-paper forms like the P-100 form used by non-transport responders, i.e. firefighters who are not equipped with laptops, in San Francisco.

Figure 1. Incident list (left) and Patient Care Report (right)

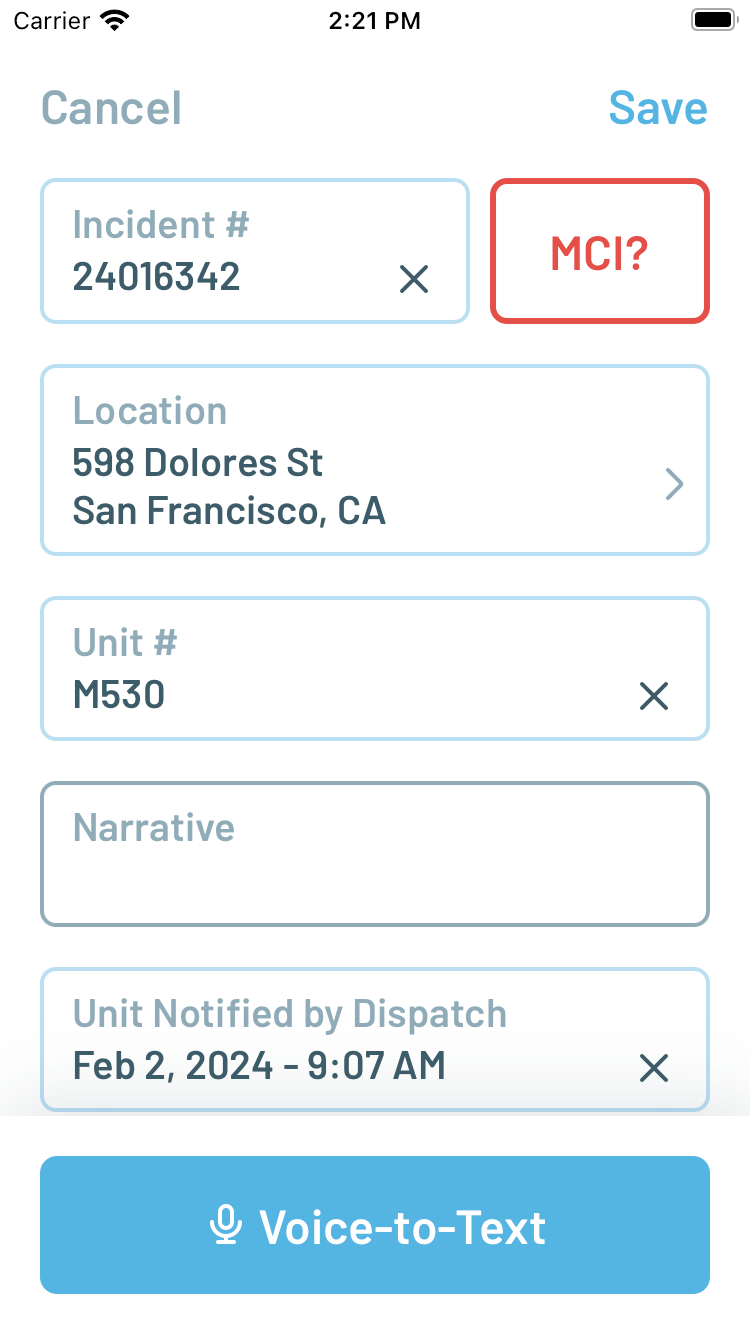

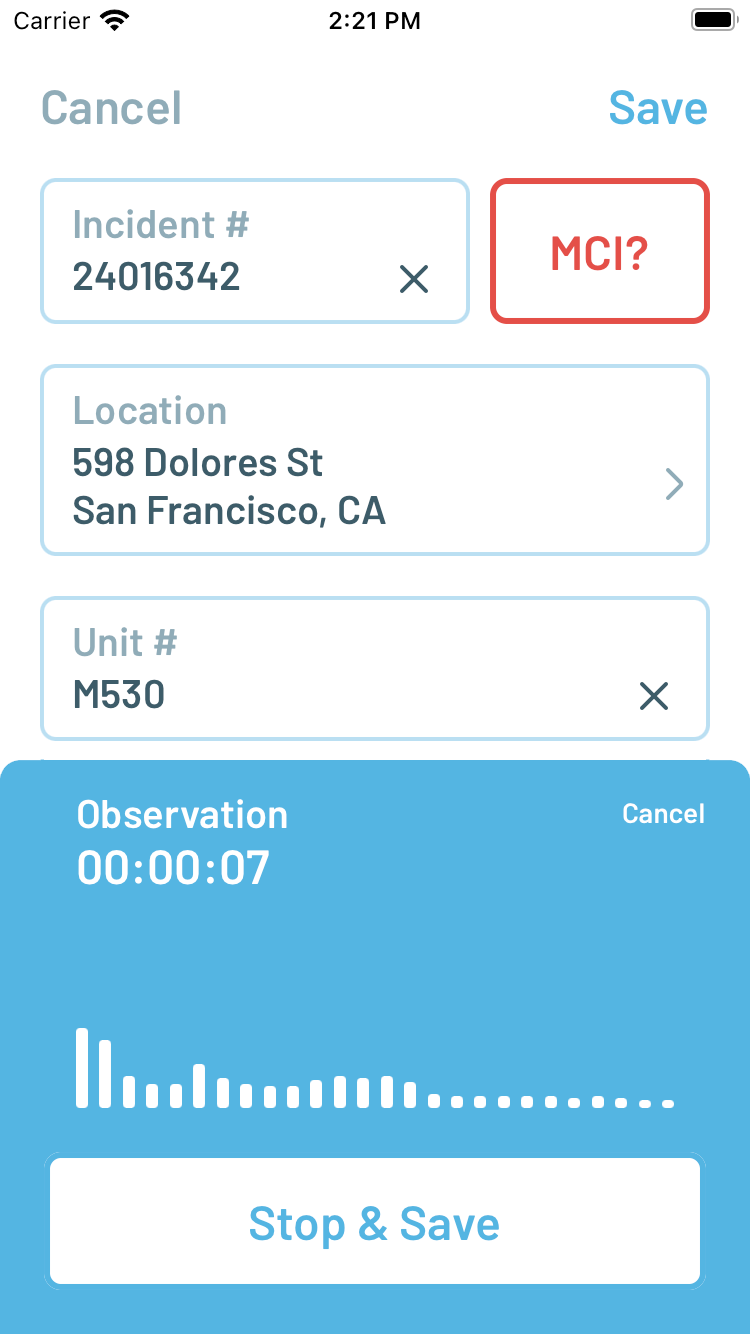

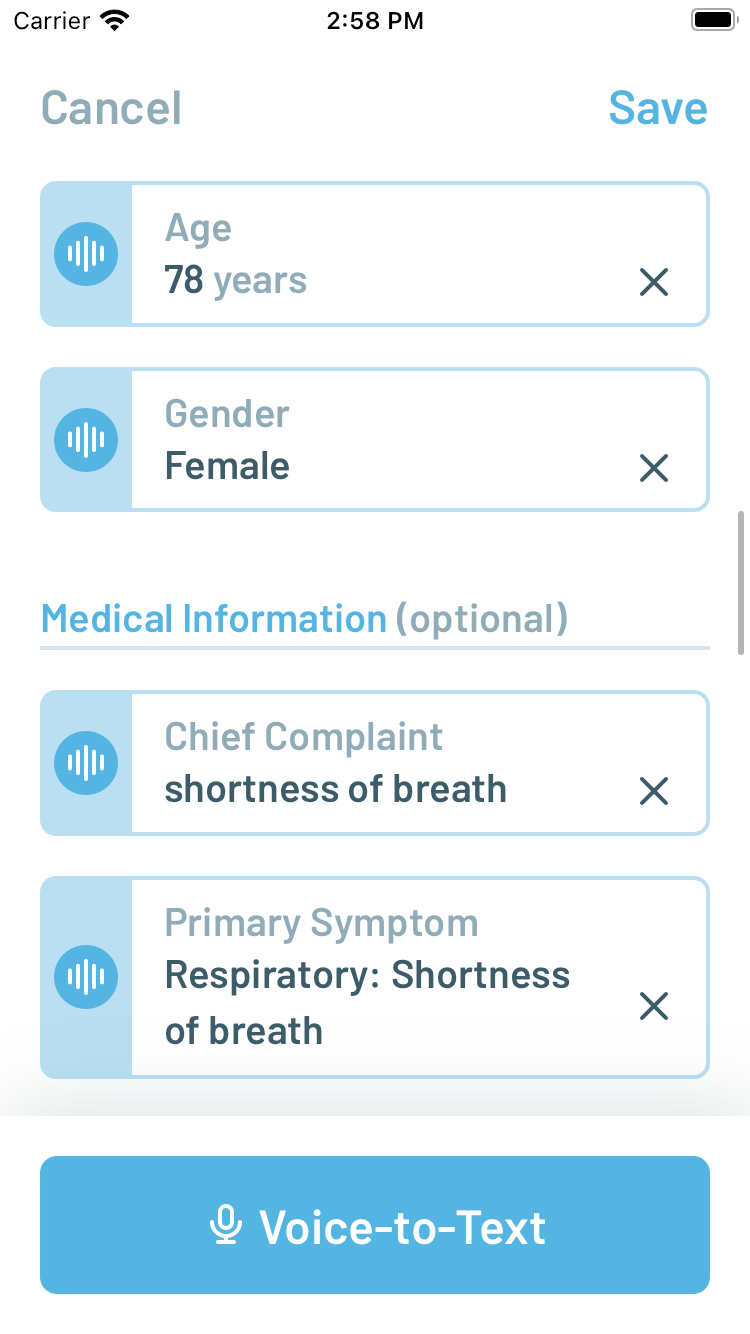

As a mobile app that runs on Apple iPhone smartphones, Peak Response can be easily carried by first responders even in situations where larger and heavier rugged laptops may be inconvenient or dangerous, such as on the side of a busy road. The ability to capture patient signatures in Peak Response was informed directly by an anecdote from a San Francisco paramedic who was forced to hike back down and up 7 stories in a building to retrieve their laptop solely to capture a patient’s refusal of treatment and transport. To further streamline the process of patient documentation, Peak Response supports voice-to-text transcription to allow first responders to dictate their observations as a narrative. The app then applies heuristics to perform a best-effort extraction of structured data from the narrative directly into individual fields in the electronic record.

Figure 2. Voice-to-Text transcription (left) and structured data extraction into fields (right)

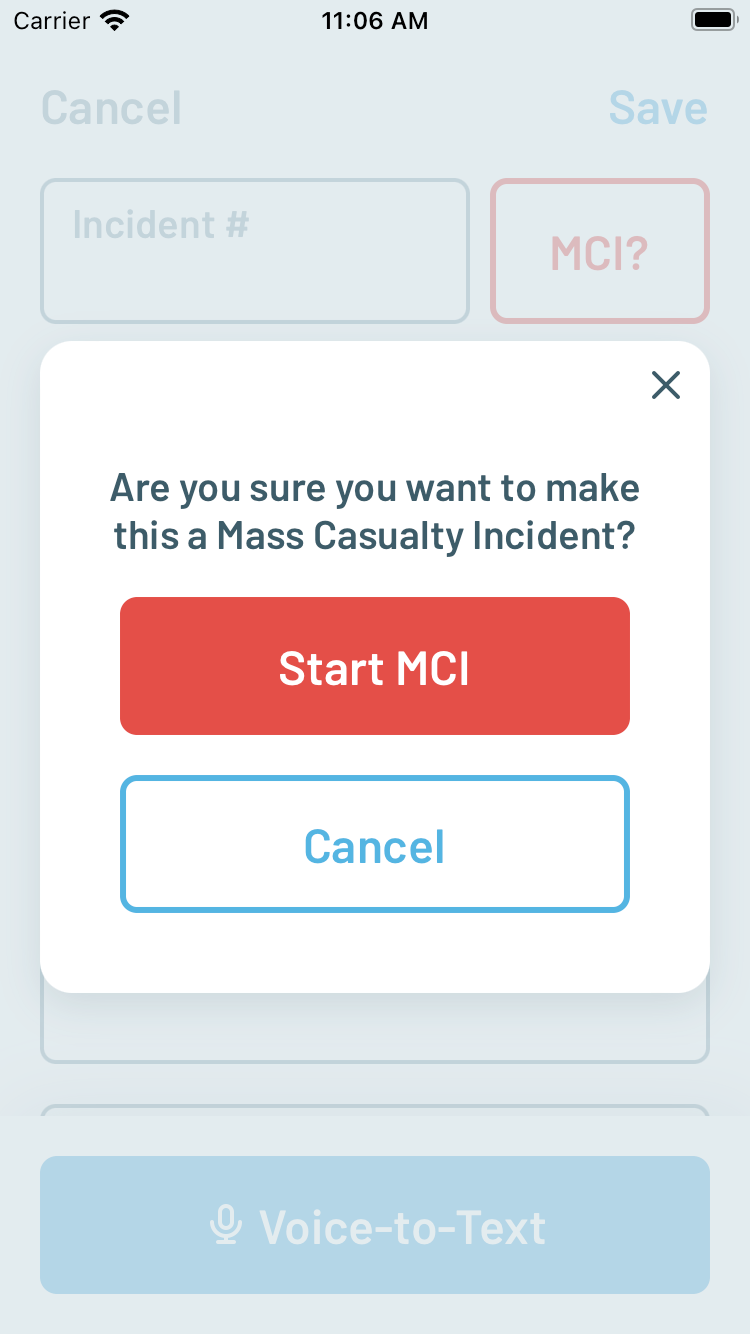

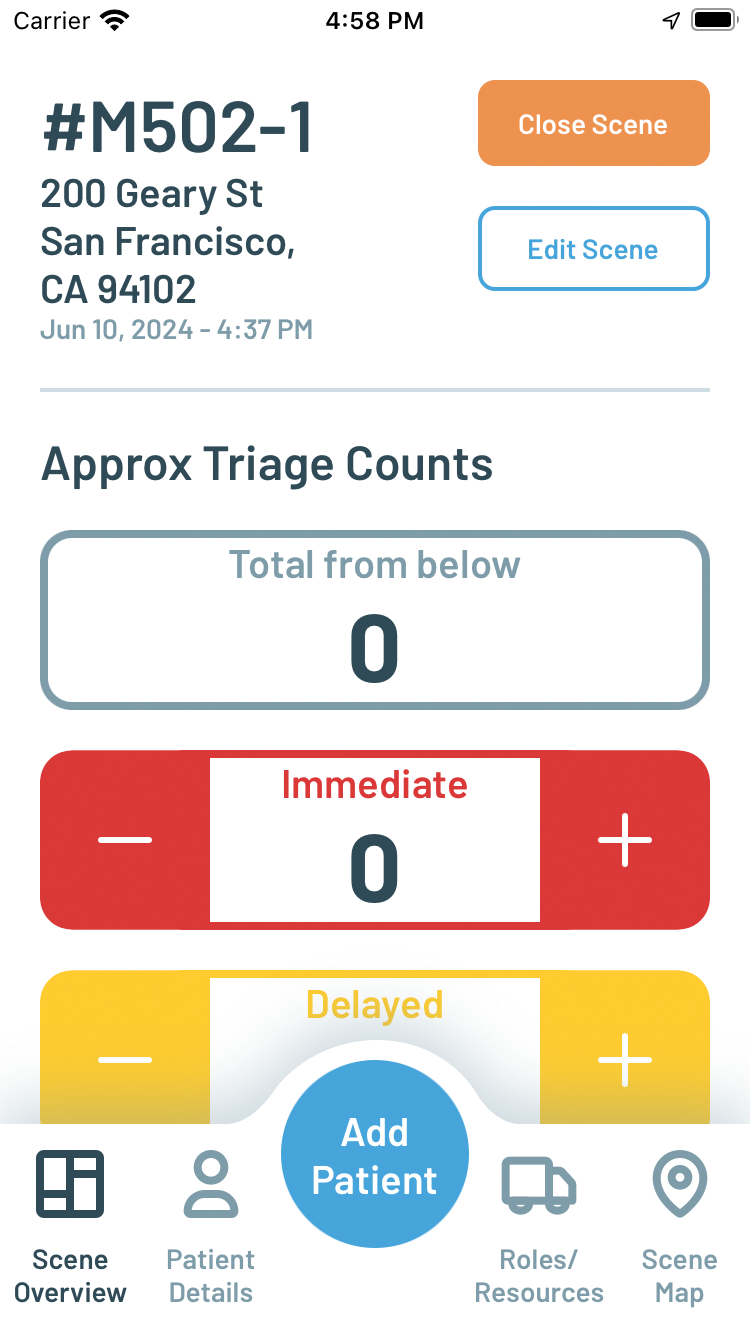

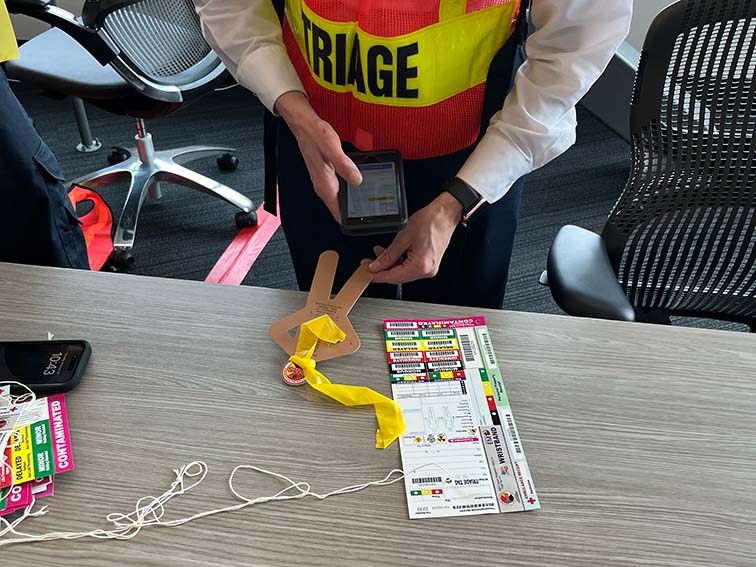

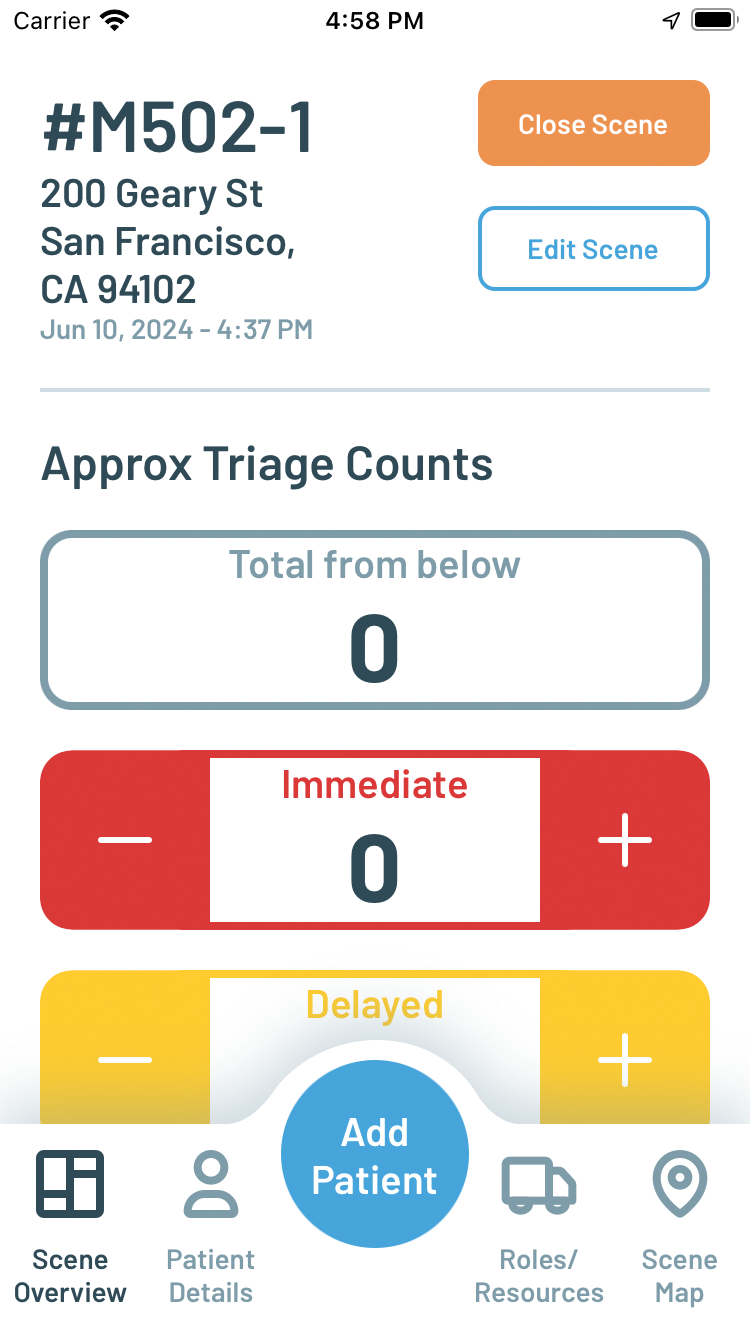

By supporting day-to-day use cases with the Peak Response app, it ensures that first responders have the opportunity to become familiar and trained with its user interface so that its usage, ideally, becomes second nature even in the case of a MCI. At the touch of a button, the Peak Response user interface becomes a real-time situation awareness tool for EMS first responders on scene of a MCI. The Scene Overview screen provides an interface for quickly recording an estimated count of patients of different initial triage priority levels by tapping plus (+) and minus (-) buttons to increment and decrement counts, respectively. For example, as first responders are sizing up the scene and evaluating patients, they may be attaching and collecting pieces of colored ribbons for tracking while an appointed Triage Leader could use the app to increment the corresponding counts.

Figure 3. Initiating MCI scene management (left) and Scene Overview (right)

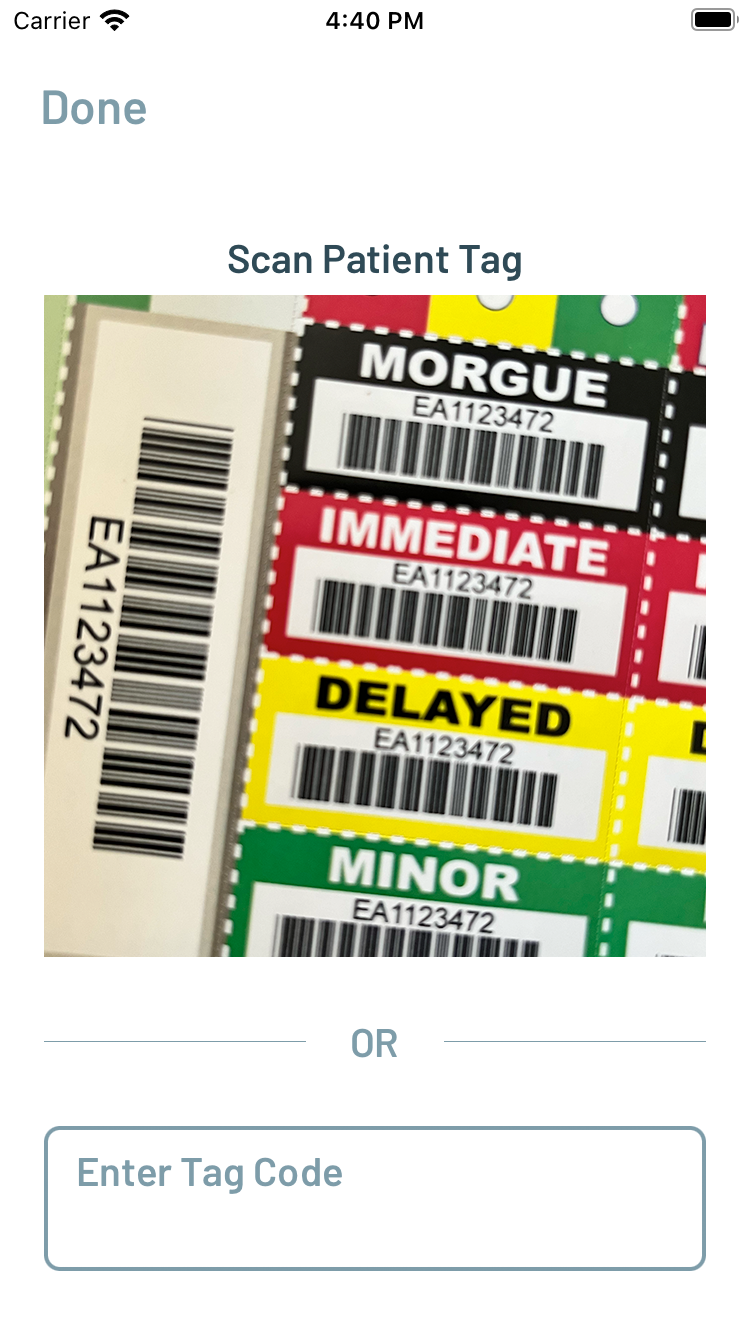

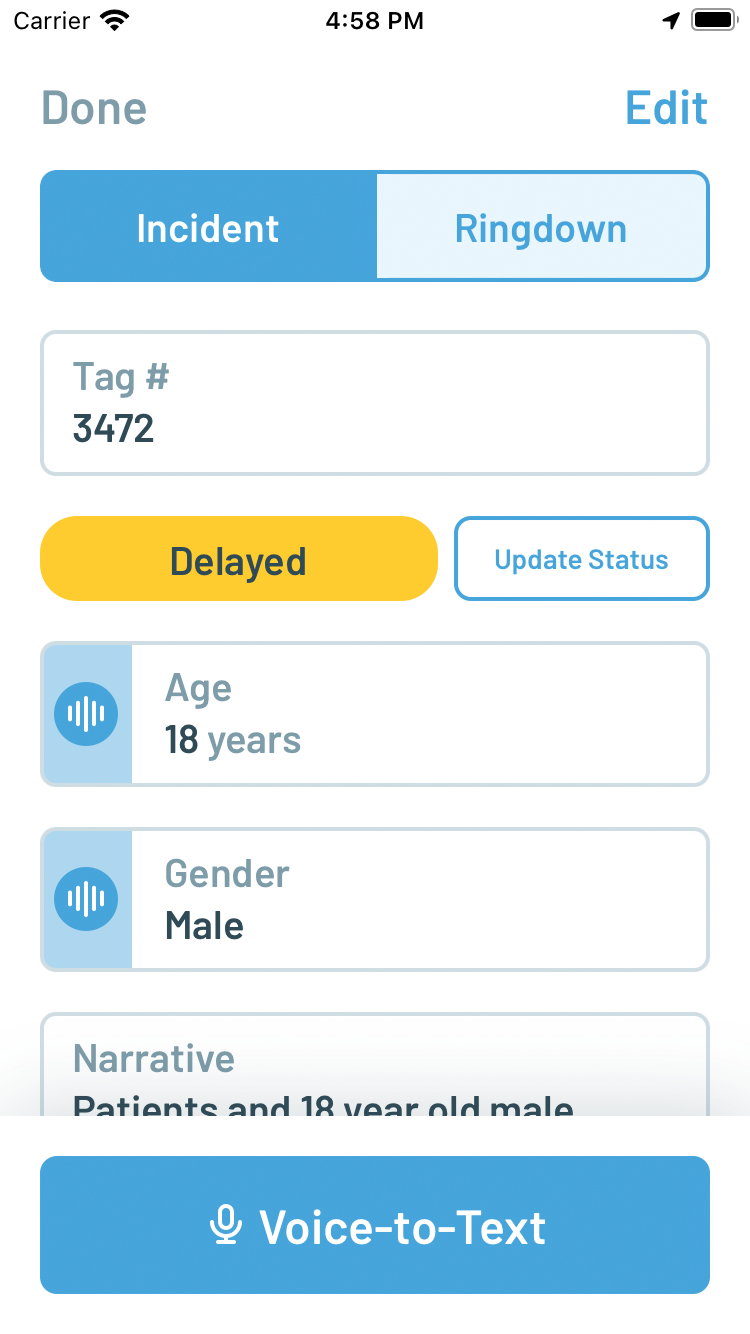

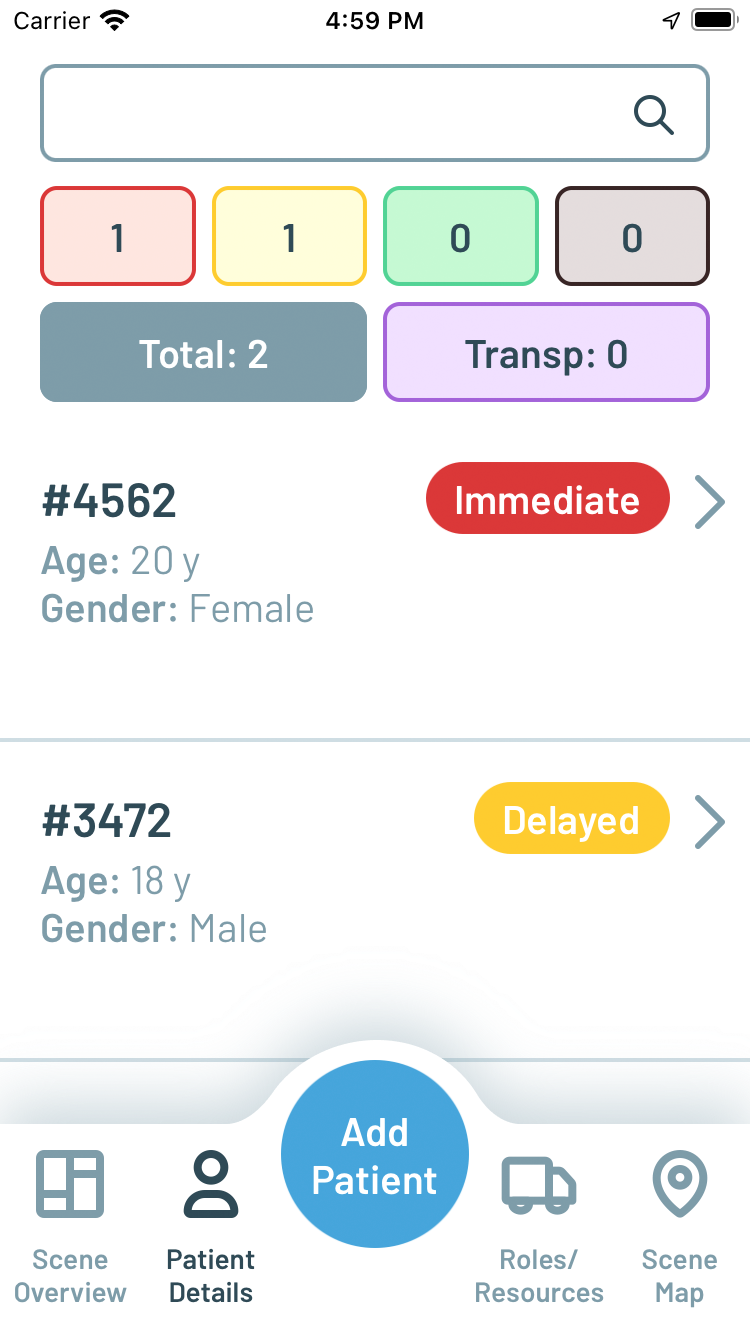

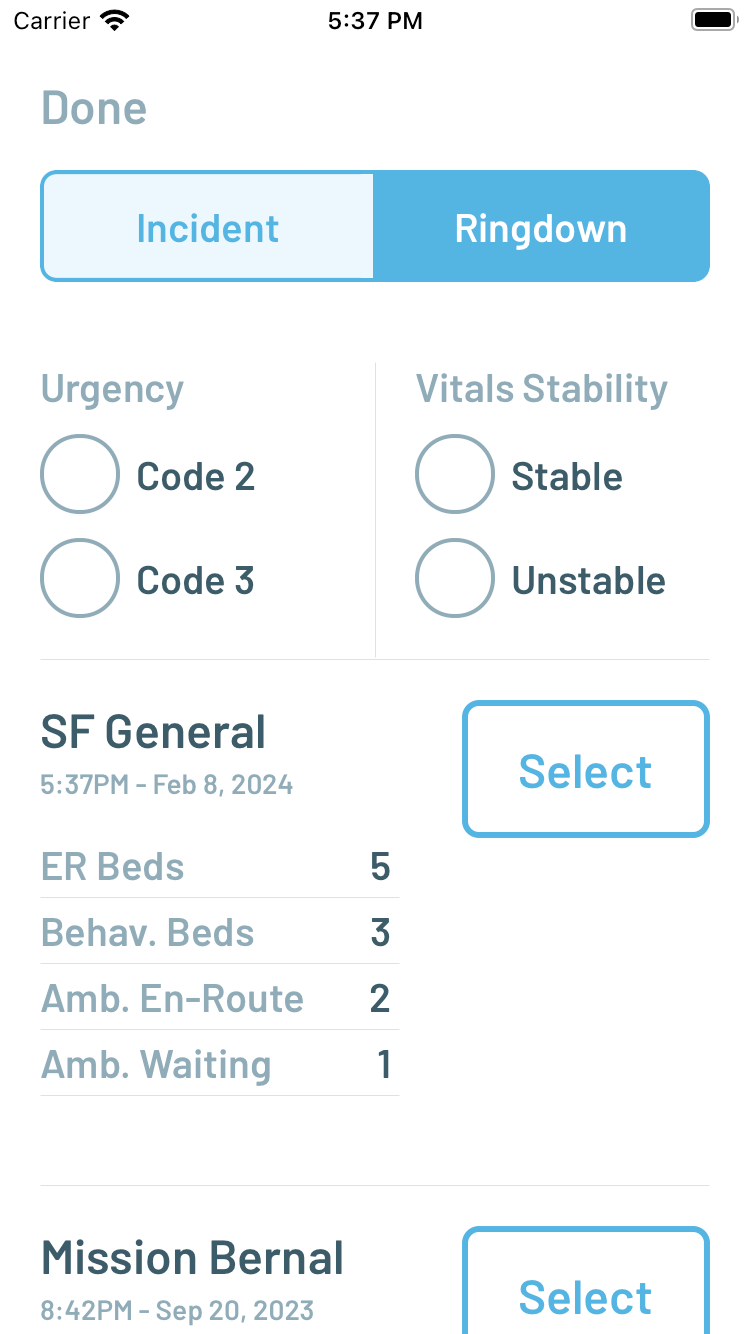

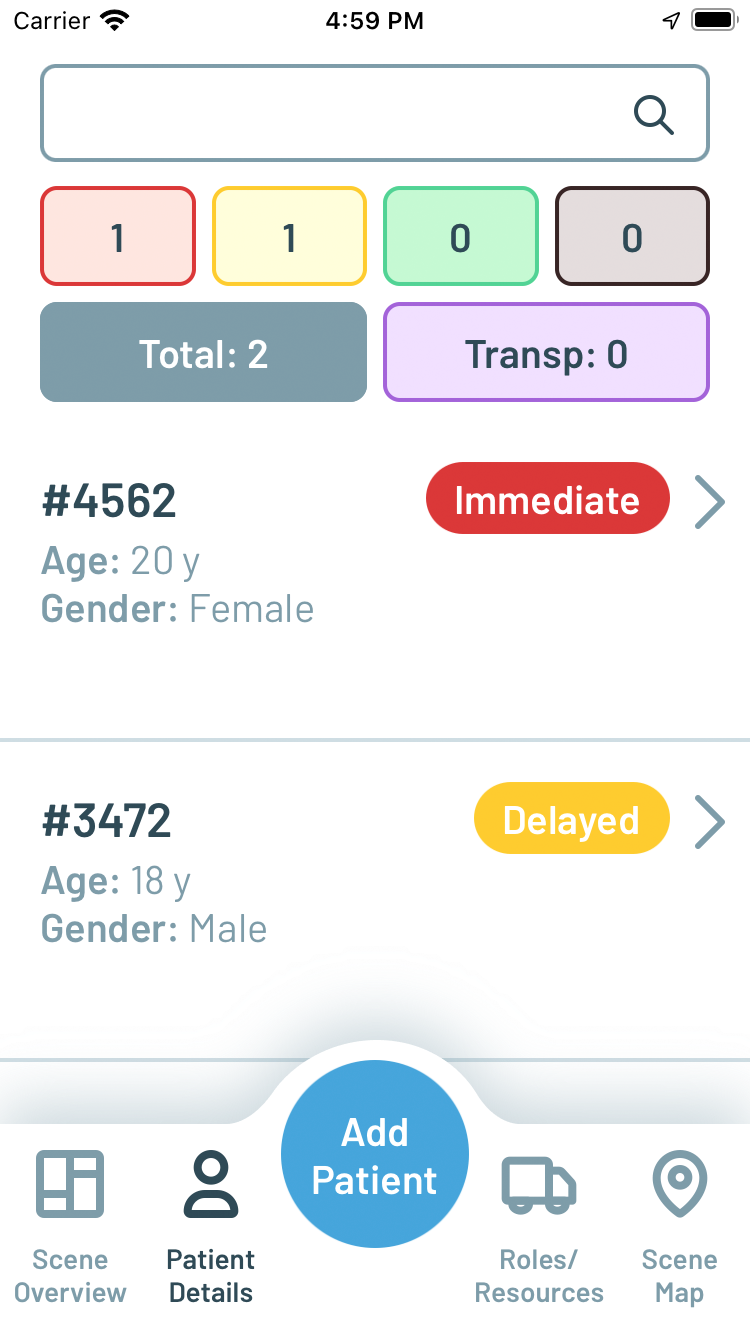

As patients are moved off the scene to designated treatment areas, they are typically given a triage tag with a barcode to track their identity. The Patient Details screen allows the user to scan triage tag barcodes and associate an electronic patient record using the same voice-to-text with data extraction interface used in the day-to-day patient documentation use case. These records form a priority sorted list of patients and are automatically aggregated into secondary triage counts. Once created, a patient record can be opened by scanning the same barcode again or by searching and tapping on its item in the list. A patient record can be associated with a transport destination, such as a hospital, by switching to the Ringdown tab and selecting the destination in the corresponding list. The act of recording this association then also sends a notification to the destination that can be viewed in a web application interface accessible from any desktop or mobile browser.

Figure 4. Scanning a triage tag barcode (left) and creating a Patient Care Report with Voice-to-Text (right)

Figure 5. Priority sorted Patient list (left) and Ringdown destination selection (right)

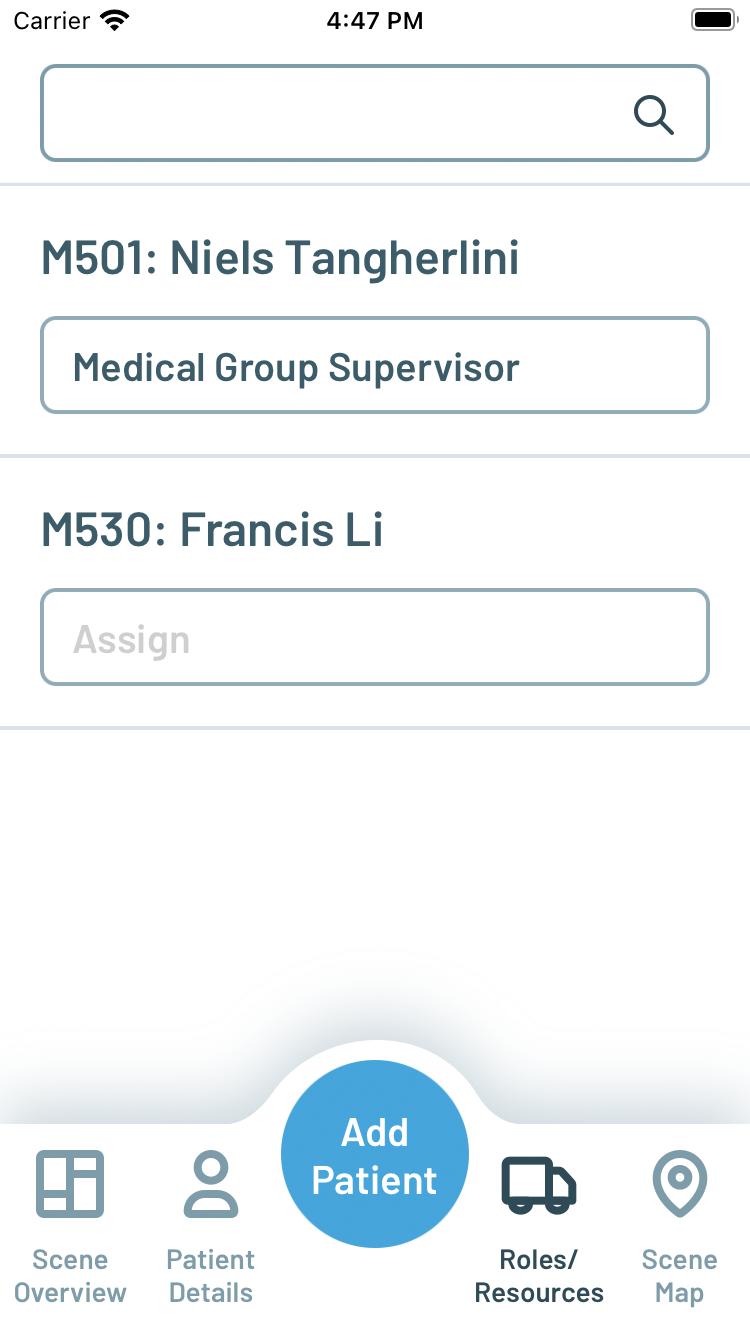

Other screens in the real-time MCI situation awareness interface include a Roles/Resources screen for identifying the units on scene with the app with the ability to assign specific leadership roles in the incident command structure (i.e. Triage Leader, Treatment Leader, Transport Leader, etc). Finally, a Map screen shows the location of patients, whose latitude/longitude coordinates are captured and updated every time their corresponding barcode is scanned with the app.

Figure 6. Roles/Resources screen (left) and Scene Map screen (right)

Tabletop MCI Drills and App Evolution

Over the course of three months from February through April 2024, the Peak Response app was presented to and evaluated by a team of six paramedics from the San Francisco Fire Department through a series of MCI drills, including six tabletop drills and one small scale drill staged in a parking lot with mannequins. Observations and feedback from each drill session were used to make direct improvements to the design and capabilities of the app before the next in an iterative fashion.

Figure 7. Tabletop MCI exercise

Figure 8. Small scale drill with mannequins

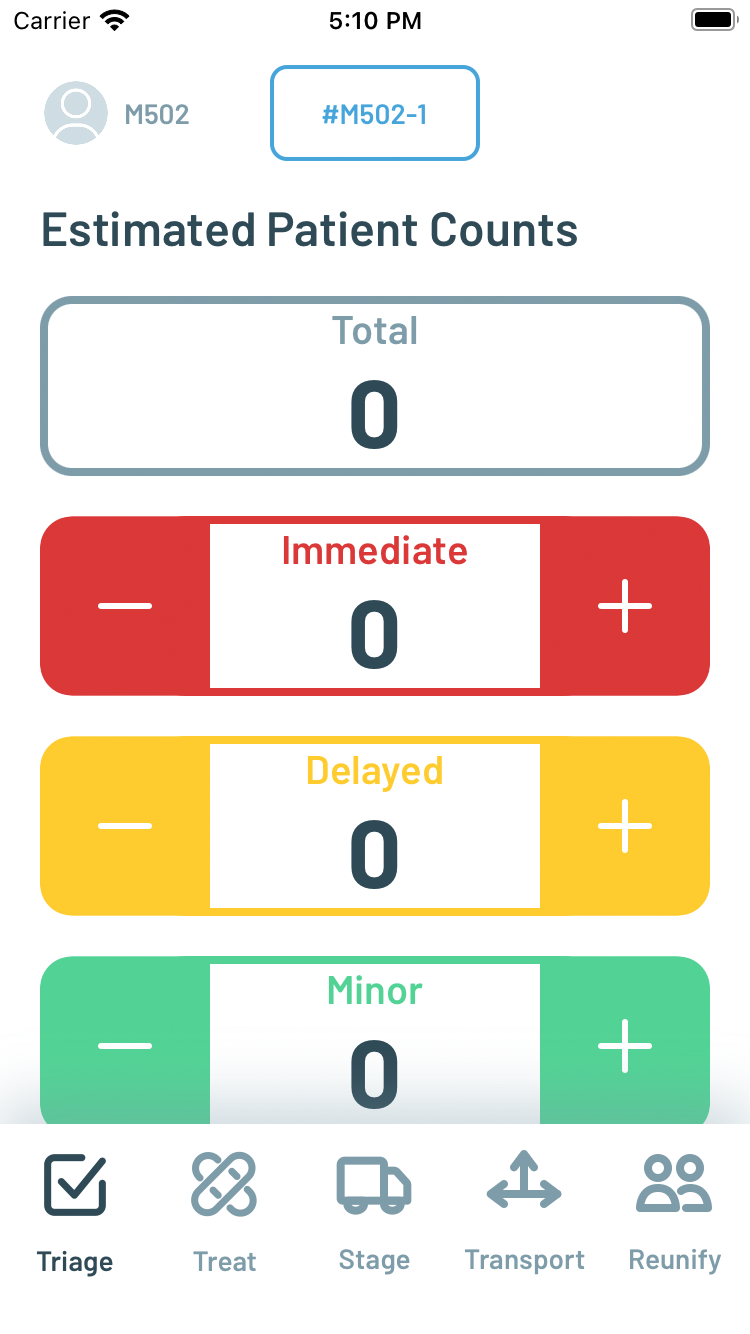

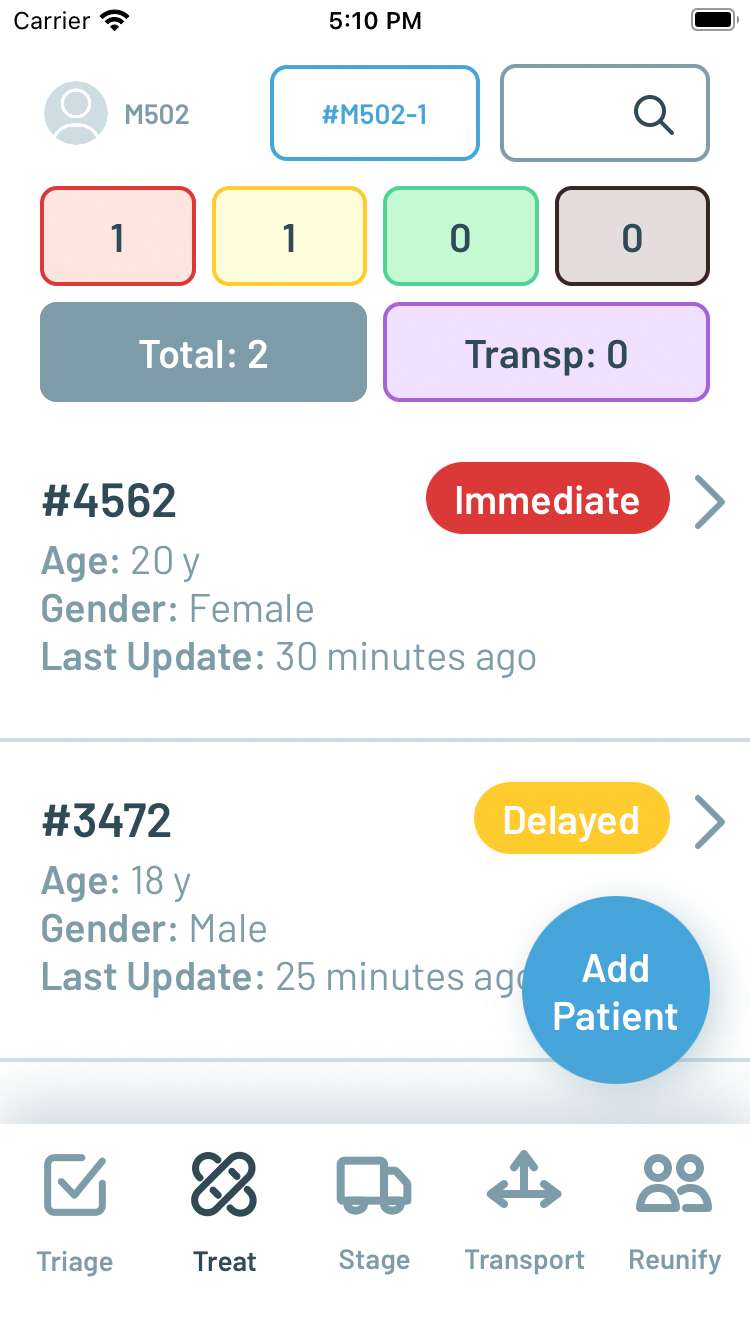

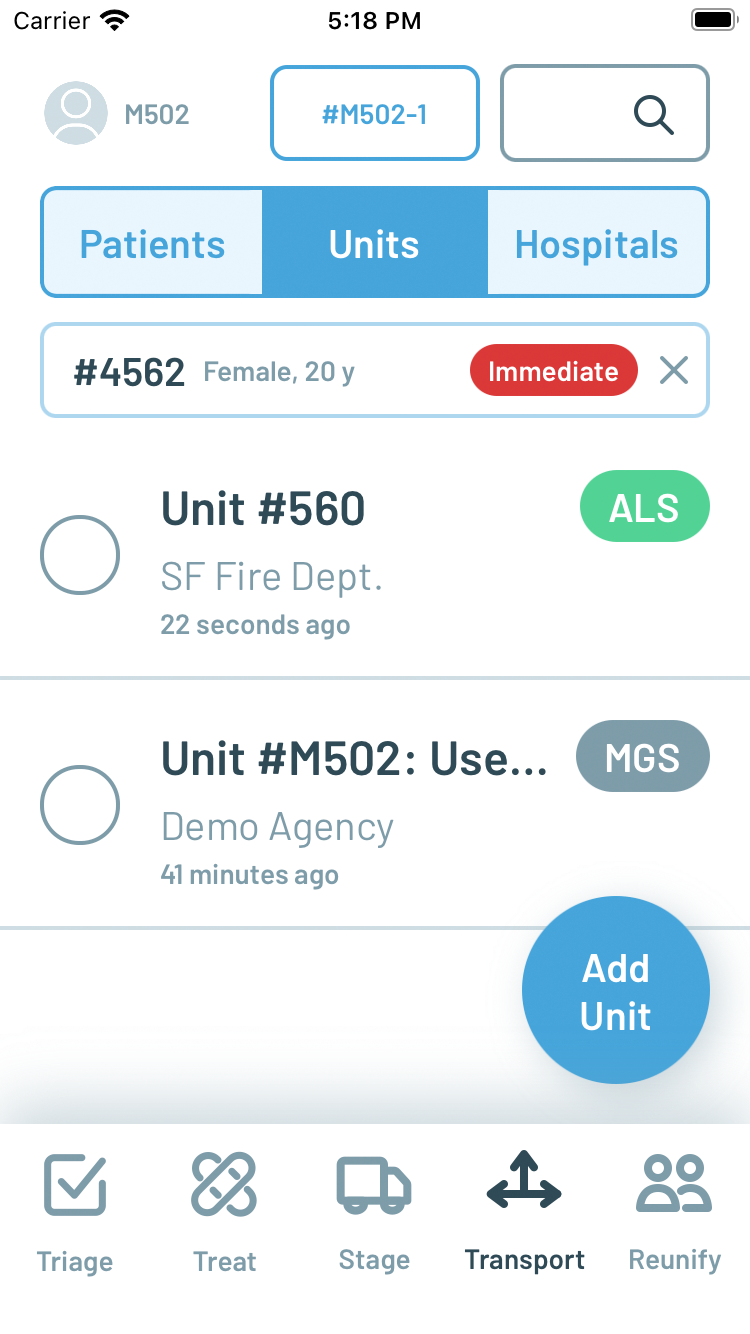

The first change was a reorganization of the tab bar to more directly reflect the functionality designed for first responders in different roles or phases of the incident- Triage, Treat, Stage, Transport, and Reunify. The Triage screen, intended to be used for the initial size-up and triage of the scene, replaces Scene Overview and shows only the Estimated Patient Counts controls. The Treat screen replaces Patient Details but with the same functionality to scan triage tags and add patient records as victims are moved from the scene to designated treatment areas. The Add Patient button, previously a permanent part of the toolbar, becomes a floating button located where it can still be easily reached by a thumb on the same hand holding the phone. Separated from the toolbar, the floating button can change its function contextually depending upon which screen is active.

Figure 9. Scene Overview and tab bar before (left) and after testing and feedback (right)

Figure 10. Patient Details screen before (left) and after testing and feedback (right)

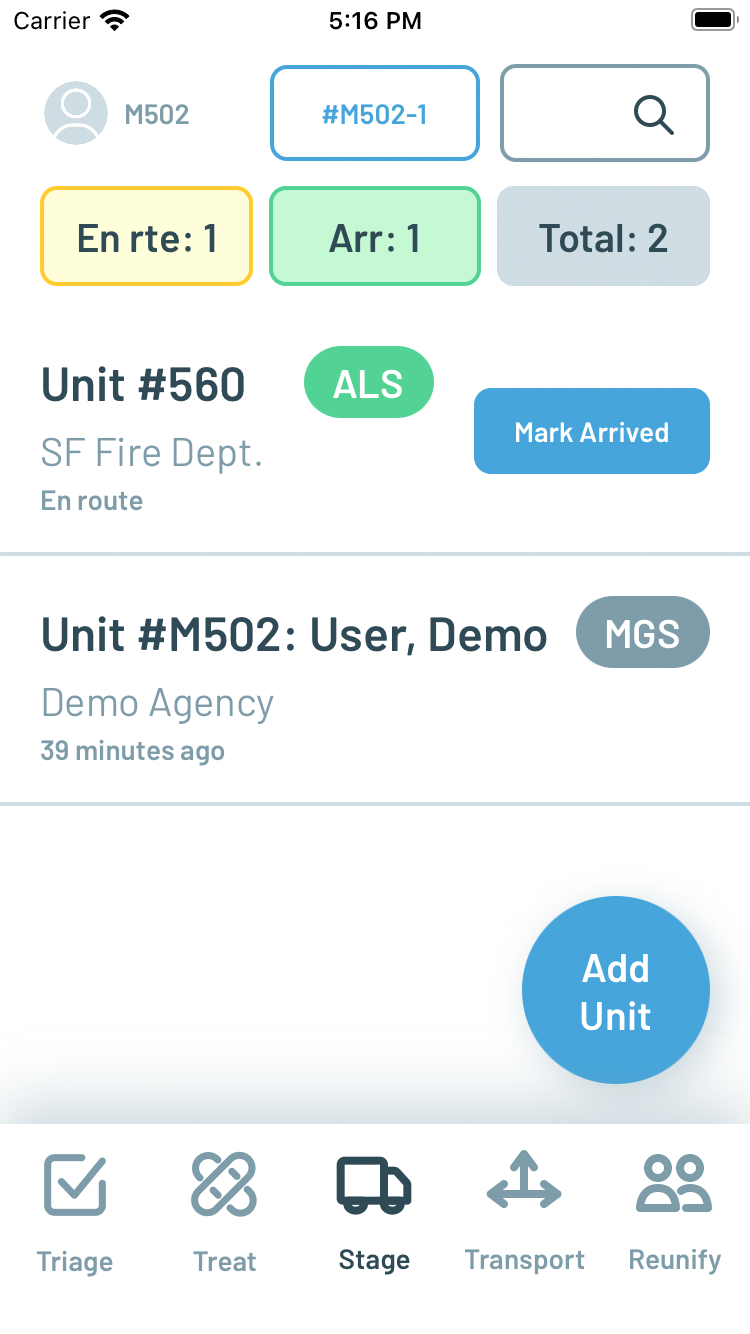

Stage is a new screen added specifically for larger MCIs where there may be a separate Staging Leader assigned to coordinate the arrival of ambulances on scene. Depending upon the logistics of the physical environment of the scene, the staging area where ambulances arrive could be some distance away from the treatment areas. Stage lists ambulance units dispatched to the scene, and here the floating button changes to Add Unit, to manually add any non-dispatched units or if there is no integration with computer aided dispatch to automatically populate the list.

Figure 11. New Stage screen (left) and ability to add units to Stage list (right)

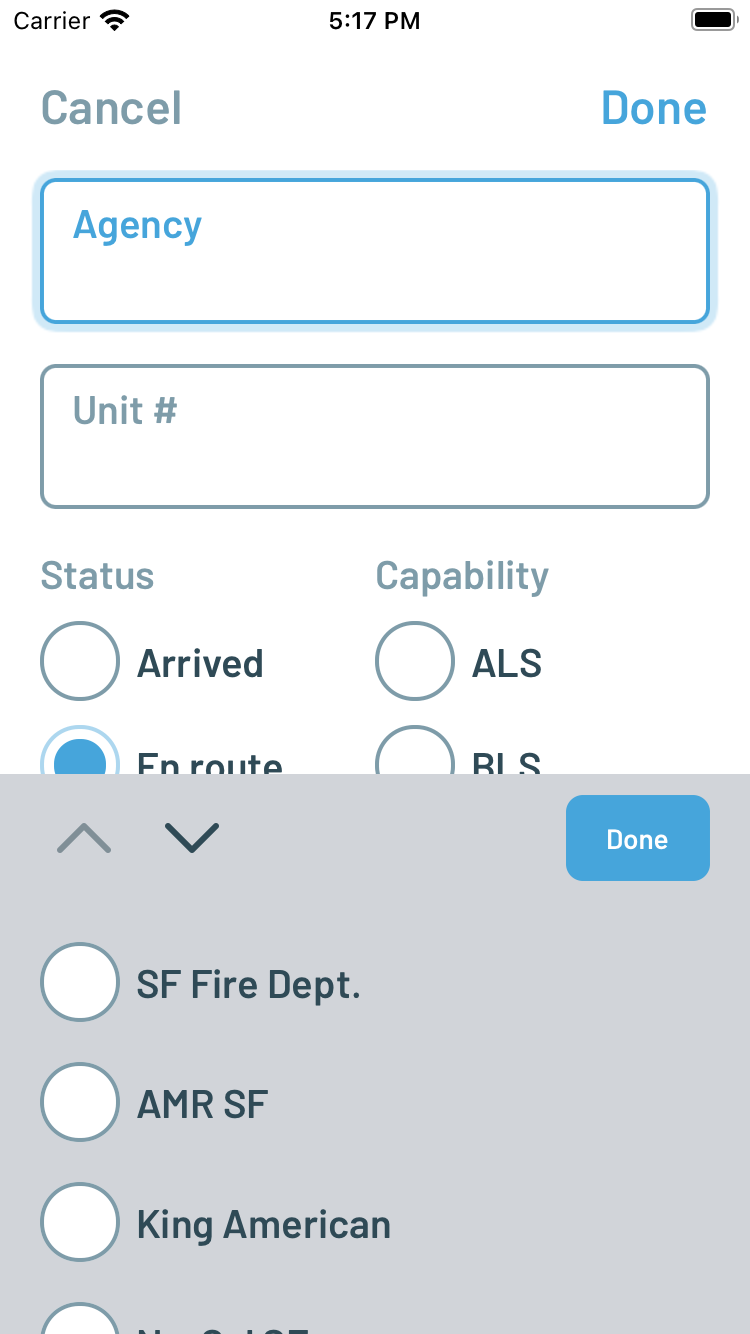

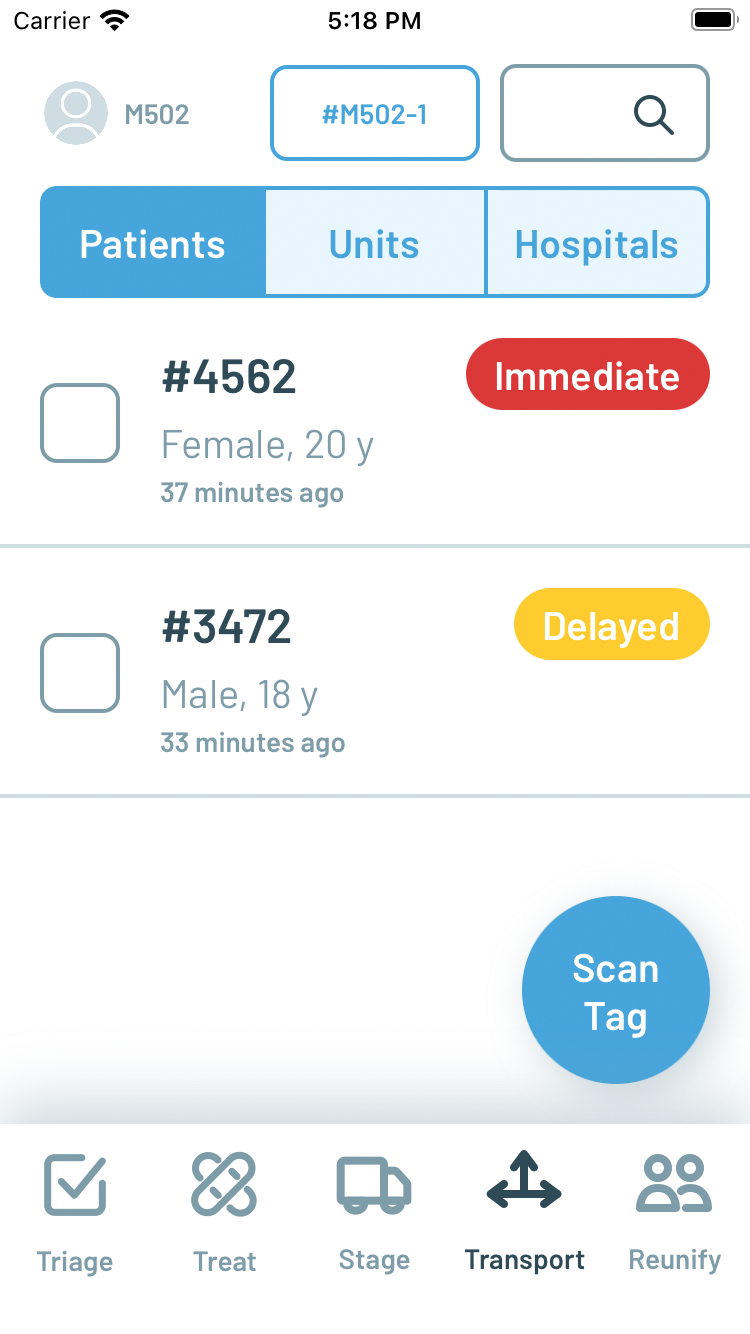

Transport is also a new screen designed specifically from feedback and observations made during the tabletop drills. Whereas in the original Peak Response design it took multiple steps to find and open a patient record in the Patient Details list and then select a destination (with the assumption that the user is the transporting ambulance unit), the Transport interface is designed to allow a Transport Leader or similarly assigned scribe/assistant to quickly confirm the association of patients with ambulance units and destinations in a simplified three-step flow. One paramedic likened the process as creating a shopping cart of information to collect and checkout repeatedly, which helped inspire the simplified design.

Figure 12. New Transport screen selecting Patients (left) then transporting Unit (right)

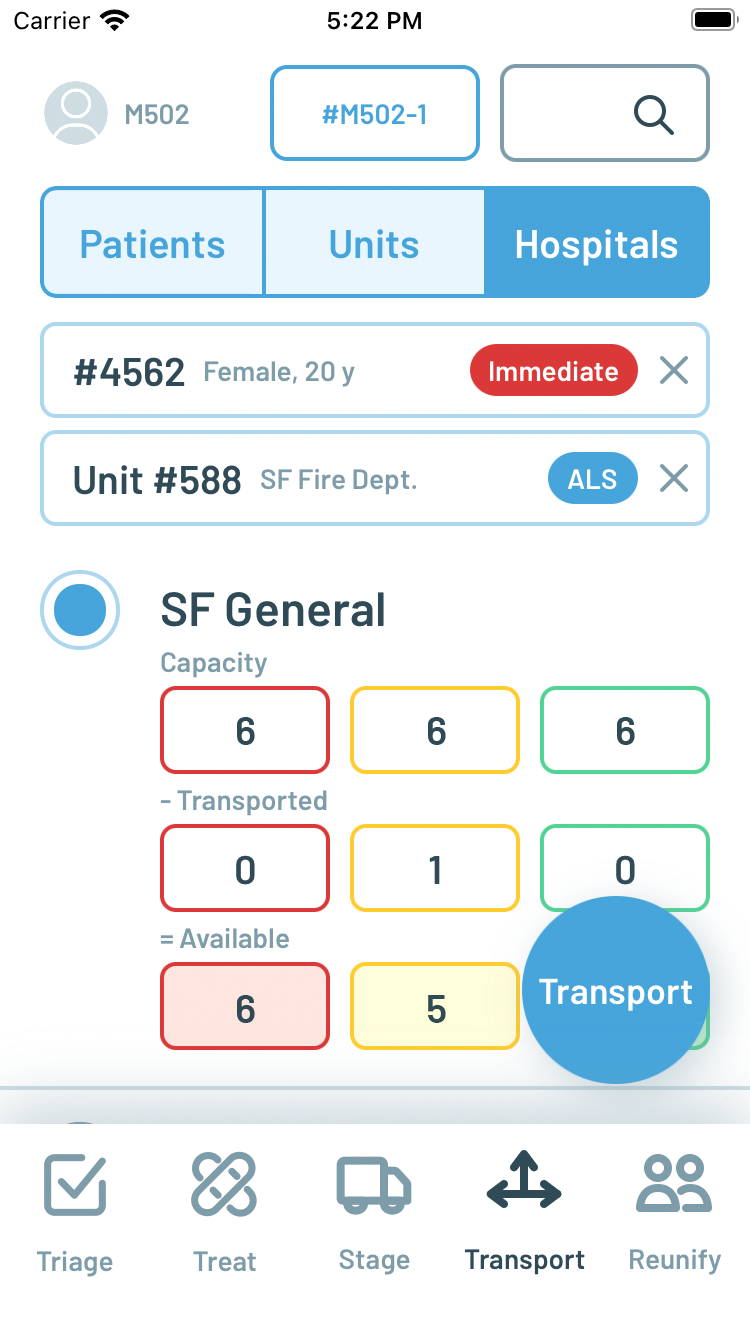

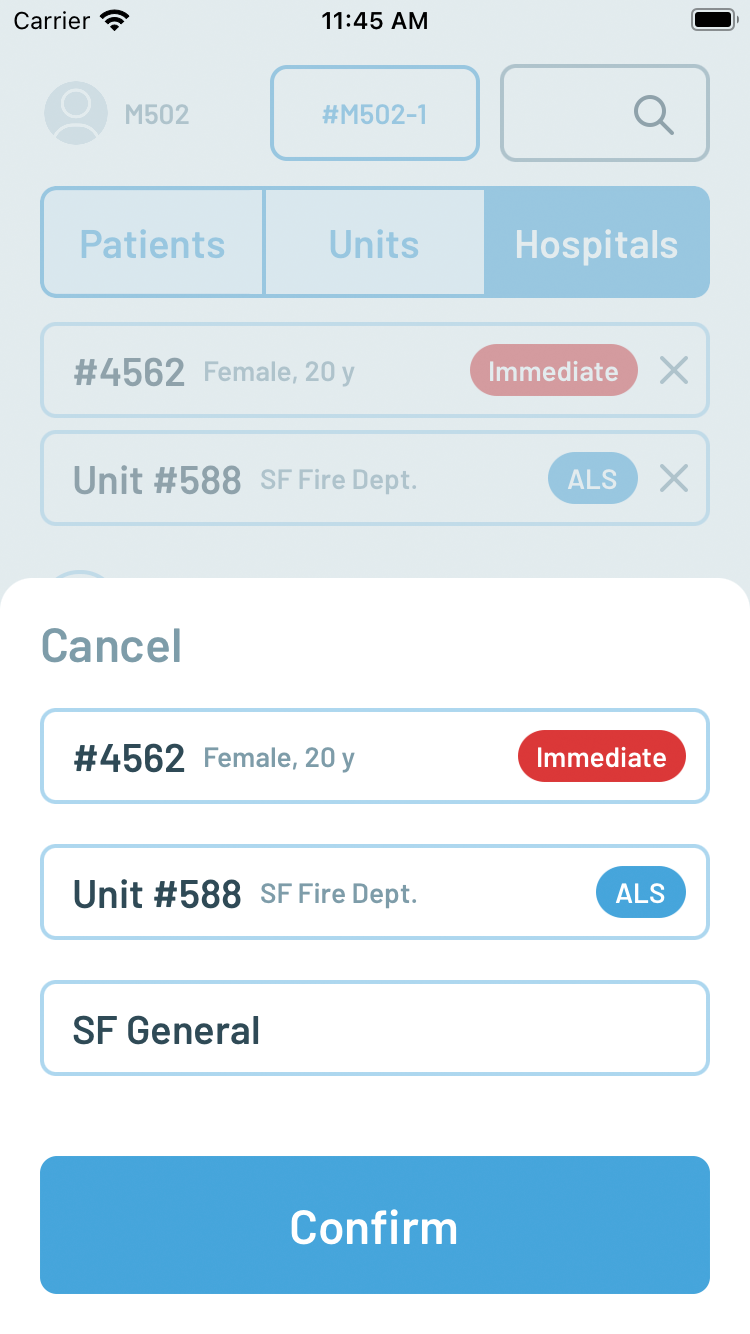

Transport contains a top tab bar to switch between lists of Patients, Units, and Hospitals, respectively. The Patients list contains the same records as the Treat screen, but with a more condensed presentation and checkboxes for making selections. The contextual floating button becomes Scan Patient on this list so that a patient can be selected simply by scanning the corresponding triage tag. Multiple patients can be selected for transport by the same unit in this interface, which was not possible previously. Once selected the user navigates to the Units tab, where they will see a compact confirmation of the patients selected and the same list of ambulance units managed in Stage with radio buttons for single selection. In smaller MCIs where there may not be the need for a separate staging area and coordination, the user of Transport can add ambulance units to the list by pressing on the floating contextual button which becomes Add Unit on this list. A unit can be selected simply by tapping on it, which toggles the radio buttons appropriately. Finally, by navigating to the Hospitals tab, the user can see a compact confirmation of the patients and unit selected and a list of regional hospitals.

Figure 13. New Transport screen selecting Destination (left) and confirmation (right)

Each hospital is displayed with, when available, estimated capacity counts for immediate, delayed, and minor patients in the top row of its listing. The next row displays the number of patients of these different priorities transported to the hospital. Finally, the third row calculates the available capacity based on the simple subtraction of transported patients from the initial capacity estimate. These capacity counts are entered into the system via a separate web-based interface that can run in any browser, including on hospital or dispatch workstations. Once a hospital is selected by tapping on it, toggling the radio button, the floating contextual button becomes enabled as Transport. Pressing Transport opens up a final reiteration of all the selections for confirmation.

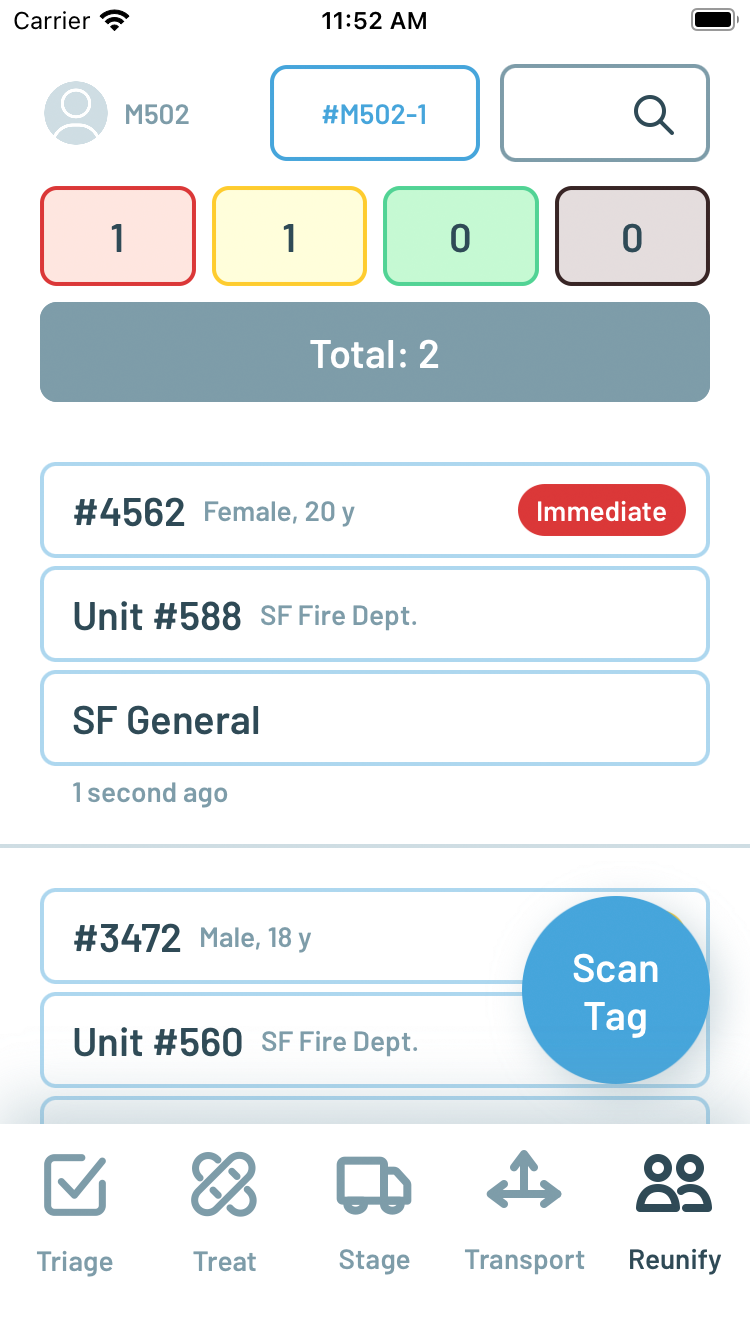

The last new screen is Reunify, which presents a searchable list of transported patients, including the ambulance unit that transported them and the final destination. This screen is intended to be used after the scene is closed, perhaps by a public information officer or other official, when families and friends of patients are anxious to know where to find their loved ones.

Figure 14. New Reunify screen

With these changes, the original Roles/Resources and Map screens were removed from the bottom tab bar. Instead, they can be accessed by tapping on the incident number button which is persistently displayed at the top center of each screen.

Large-scale MCI Drill

On April 25, 2024, a citywide MCI drill organized by the City and County of San Francisco Department of Public Health was conducted at the San Francisco State University campus. Participants in the drill included the San Francisco Fire Department, the Department of Emergency Management, and all local hospitals, including Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. As an evaluation of the city and county’s current operational readiness for a MCI, the Peak Response app was not used directly by the participants in the drill. However, the same six paramedics who participated in the prior tabletop drill evaluations were assigned proctor roles in the large-scale MCI drill observing participants in different phases of the drill, including during initial triage, secondary triage and treatment, staging, and transport. These six paramedics used the Peak Response app in parallel to capture and document actions performed and data collected during the MCI, with the caveat that they could not take any direct action in the drill themselves as proctor observers. While these conditions limited the ability to define objective measures of comparison between first responders with and without the app, it still provided a more realistic context relative to tabletop drills from which to evaluate the app’s usability and effectiveness on its own.

After the drill was started, a proctor with Peak Response followed the first responders onto the scene to observe initial triage. The setup of the MCI drill was a simulated stage collapse during a concert, with 65 patients of varying severity. As first responders began to triage individual patients on scene, the proctor with Peak Response was able to increment the corresponding patient count in the Triage screen. The first increment of patient counts was visible in Peak Response within five minutes of the start of the drill. However, a complete initial patient triage count was never completed- an approximate total count of 50 patients was reported over the radio by the participating responders and patients were moved quickly off the scene to treatment and transport without more detailed tracking. From this experience, it was later suggested by this proctor to add a manually entered estimated total patient count to the Triage screen independent of the separate priority counters that are automatically summed into a calculated total.

Figure 15. Simulated concert stage collapse and victims

Figure 16. Treatment area

Three different proctors with the Peak Response app entered patient records in the Treat screen during the drill. The proctor observing initial triage left the scene to join the proctor in treatment entering patient records so that they could collectively keep up with the flow of incoming patients. A third proctor was stationed at the minor/green treatment area to enter records for the “walking wounded” that were able to leave the scene on their own. These proctors effectively functioned in a manner similar to participating responders assigned to be “scribes,” with the exception that Peak Response allows multiple scribes to enter data in parallel, as opposed to pen/paper/clipboard/whiteboard practices in which there is typically only a single scribe recording data and notes. The proctors using Peak Response were able to enter patient records quickly using the voice-to-text interface and ultimately document all the patients on scene.

A fourth proctor with Peak Response was stationed in a simulated dispatch center located in a conference room adjoining the scene. This proctor was able to listen for the simulated dispatch of units to the scene and enter them as enroute in the Stage screen of the Peak Response app, effectively simulating a computer aided dispatch integration. A fifth proctor with Peak Response was stationed at a parking lot a short distance away from the scene where waiting ambulances were timed for release and arrival on the scene. As ambulances departed the parking lot the proctor was able to mark those units as arrived in the Stage screen, making them available for selection in the Transport screen. A notable insight gathered from this usage of the app is the need to reconcile ambulance radio call sign ids with numbers displayed on the outside of the vehicles. While the SFFD has dedicated vehicles for each call sign such that the call sign matches the number on the vehicle, the private ambulance companies had separately numbered vehicles assigned to their call sign ids per their own vehicle inventory practices. As a result, proctors on scene had to verify and confirm with each ambulance crew their assigned radio call signs.

The sixth proctor with Peak Response was assigned to observe transport, and was able to use the Transport screen in Peak Response to confirm the patient identifier, transporting unit, and destination hospital for every patient leaving the scene. As the pace of transport increased, they enlisted the help of one of the proctors in treatment to assist in the process, again highlighting the ability for Peak Response to help parallelize the record-keeping process in a way not possible with a singular scribe attempting to capture all the patient barcodes and notes in a single clipboard worksheet. Furthermore, as transport is confirmed in Peak Response, a notification is automatically pushed to a corresponding web interface designed for the hospital. The Peak Response notification of the first patient transport to Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital captured by the proctor on scene was delivered to the hospital approximately 10 minutes in advance of the same notification relayed by the participating transport leader over radio through dispatch.

In addition to the proctors, representatives from the FirstNet Authority and guests from Hyannis Fire Department in Massachusetts were also present, and they were loaned iPhones with Peak Response in a view-only mode so that they could watch the data being collected in real-time appear in the app during the drill. Anecdotally, having the Peak Response app gave them insight into the performance and progress of the participating first responders on scene that they would not otherwise have if they relied solely on radio and what they could observe firsthand. One observer reflected:

… It beats the clipboard, radio, and face-to-face [interaction] by saving time and being instantly available anywhere needed. There is no extra and redundant voice activity and radio clutter needed to get the information, if updated correctly. It’s very helpful for the IC to keep an eye on staged resource counts if unable to see the staging area, and prevents losing patient information or awareness of transport status which is always a difficult task.

And another observer shared:

… the Peak Response app surpassed my expectations. It seemed to be a very efficient way to collect information on patients. I was aware that there were a few instances of duplicate patients, however, they were quickly recognized. … If we gain the ability to pair Peak Response with [our EPCR system], I think this product would drastically minimize the time spent collecting demographics on patients.

There was an overcount with some duplicate records for patients created, but ultimately there was some confusion introduced by the design of the drill. Patients on scene were not being physically transported to actual hospitals, but instead “notional” transport was used to report numeric patient identifiers to hospitals so that they could simulate the arrival of corresponding patients. Patients wore these identifiers on cards containing their symptoms, and as a result, some participating responders on scene used these identifiers in lieu of attaching a separate triage tag with barcode typically used to identify a patient in a MCI. Without a triage tag barcode to scan, proctors with Peak Response entered the symptom card patient identifier instead. As the drill progressed, however, responders were instructed to attach triage tags with barcodes to better simulate an actual MCI, since people in real life do not have convenient numeric identifiers already hanging around their necks. As a result, some patients in the drill were entered twice, once by patient symptom card identifier and again by triage barcode tag number. As a result, a number of new and enhanced features for Peak Response were suggested by the proctors and observers, including the ability to archive/delete patient records determined to be duplicative and the ability to attach photographs to help with the identification and de-duplication of patient records.

EMT Student Training and App Insights

In the week following the large-scale MCI drill, Peak Response was also tested with 18 students at the City EMT training academy in San Francisco. On Thursday, May 2, 2024 a classroom introduction and training session with Peak Response was conducted, followed by MCI training drills using inflatable mannequins. Anecdotally, many students were very excited by the potential of using Peak Response, which was expected from a younger generation more accustomed to using mobile apps in their day-to-day lives. During the MCI training drill with mannequins outdoors, it was observed that, similar to the proctors in the large-scale drill, students were able to parallelize their work when using Peak Response. In particular, as the practicing transport leader was starting to become overwhelmed by the number of patients, they were able to assign two additional students to help ensure proper recording and capture in the Transport screen of the app.

Figure 17. City EMT tabletop MCI training exercise

Figure 18. City EMT MCI practice drill

A few days later on Saturday, May 4, 2024, a larger simulated MCI training drill using a combination of mannequins and volunteer victims was conducted both without and with the Peak Response app, with supervision and proctors from the San Francisco Fire Department and other local ambulance companies. Three rounds, or evolutions, of the drill were conducted. The first evolution, without the app, was considered a practice/warm-up. Then, a second evolution without the app was performed, followed by a lunch break, and then a third evolution using the app. Between the latter two evolutions, timestamps were recorded during the drills to mark significant milestones including the arrival of first responders on scene, the declaration of a “red alert” and request for resources, the movement of the first patient to treatment, the transport of the first red priority patient, the transport of the last red priority patient, and the end of the drill. Following the drills, a survey was administered to the students to capture their subjective impressions of their performance during the drills, both without and with the app.

There were no significant differences in the timings between evolutions without and with the app, with the exception of the time from first patient treatment to all red patients recorded and transported (19 minutes without app, 26 minutes with app). However, due to a miscommunication with the moulage team preparing the victims, there were 12 red victims in the app evolution compared to 8 red victims in the non-app evolution, for a total of 4 additional red patients to be treated, recorded, and transported. Ultimately, the amount of time spent documenting in either case was significantly overshadowed by the time physically spent moving and treating the victims. Finally, due to inclement weather, the drills were performed completely indoors so as to not subject the volunteer victims to heavy rain. As a result, the simulated treatment areas were significantly more crowded in the classroom, and unlike in the prior day’s training scenario outdoors, the students did not opportunistically parallelize their work during treatment or transport.

Subjectively, during the after-action debrief following the final evolution, the students felt that using the app during the drill made it more difficult. Indeed, as students they were more focused on practicing their skills in evaluating and treating patients under the supervision of the proctors, and often had to be reminded and prompted to use the app. This is also reflected in their post-drill survey scores which show slightly lower scores for their performance using the app, although the differences are not statistically significant. Finally, the students had significantly less preparation using the app than the paramedics serving as proctors during the large-scale drill, who had practiced regularly for almost three months in advance.

| No app | With app | p-value | |

| How efficient were you? | 3.9 | 3.6 | 0.3 |

| How accurate were you? | 4.1 | 3.7 | 0.3 |

| How clear was communication? | 3.8 | 3.4 | 0.3 |

| How well coordinated? | 4.1 | 3.8 | 0.2 |

| How useful was the app? | N/A | 4.1 | N/A |

Next Steps

Additional feature improvements and enhancements in the app based on the observations of and feedback from the participants in the drills with the San Francisco Fire Department and City EMT are under design and development. Furthermore, the experience of testing Peak Response during these drills has provided insights into how we can improve the observation and measurement of first responder performance and the impact of the app in future tests. At time of writing, planning is underway for testing the app in another large-scale MCI drill in the fall of 2024 with Hyannis Fire Department in Massachusetts.

Ultimately, however, the effectiveness of the Peak Response app and its design in an actual MCI depends upon its ability to find distribution and adoption in the public safety industry. To that end, business development discussions are underway with different EPCR software vendors to find partnership and integration opportunities so that the capabilities of Peak Response for rapid and convenient data entry can be used on a day-to-day basis with seamless data integration into other systems for reporting compliance. Peak Response already can export its data in the industry standard NEMSIS XML format to help facilitate data exchange.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend immense gratitude to Assistant Deputy Chief Niels Tangherlini and the personnel of the San Francisco Fire Department along with Rick Segura and Adam Babendir and the staff and students of City EMT for their participation in the preparation, practice, and execution of this test of the Peak Response app. Further appreciation is due to Chief Peter Burke and the personnel from Hyannis Fire for their participation as observers in advance of testing Peak Response in Massachusetts in the fall of 2024. Finally, a big thanks to Charles Hardnett, Chris Baker, and Sahna Anand of the FirstNet Authority for their support of this work. This project was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Public Safety Communications Research division (award number 70NANB21H056).